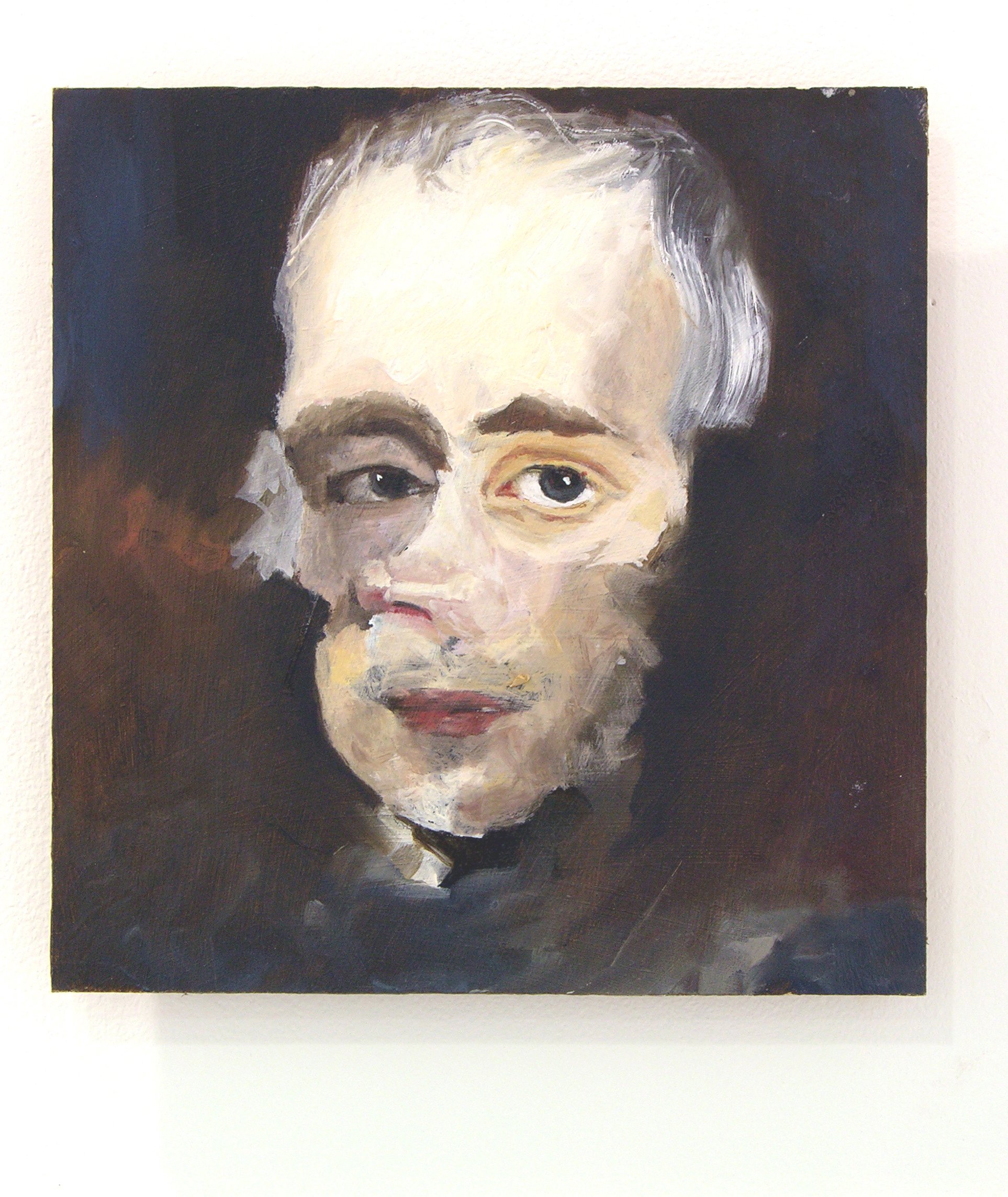

One of the key aspects of painting is the ability it affords you to manipulate and shape your subject matter. What makes painting unique is its plasticity. The plasticity of paint allows the painter to manipulate and shape the subject matter whilst simultaneously manipulating the properties of the paint itself. Through diluting, thickening, layering and obliterating, the painter has all the tools with which to interchange both subject and material - as the represented subject slips out of focus the material of paint takes charge and begins to dictate. One of the most common examples of this plasticity of paint can be found in the layering and glazing techniques of the Dutch and Spanish 17th-century painters such as Rembrandt, Velasquez and Rubens. As a contemporary painter interested in the substance of paint these Dutch and Spanish masters have always had a particular allure precisely because of the techniques they employed. How these works were painted, through the building up of layers of paint in glazes, has informed the work you see on these pages. They hold in their alchemical construction the hallmarks of the Dutch and Spanish 17th-century painting traditions.

The paintings of the Spanish and Dutch masters can’t simply be viewed as artifacts of a bygone era, however. The pertinence of these historic works lies not just in the paint’s plasticity but also in the colonial wealth that drips from these portraits. Often seen as the birth of modern society we get a first glimpse of the power of money, which was made through the trade of minerals, foods and people - this power would soon usurp the old dominance of the king and religion.

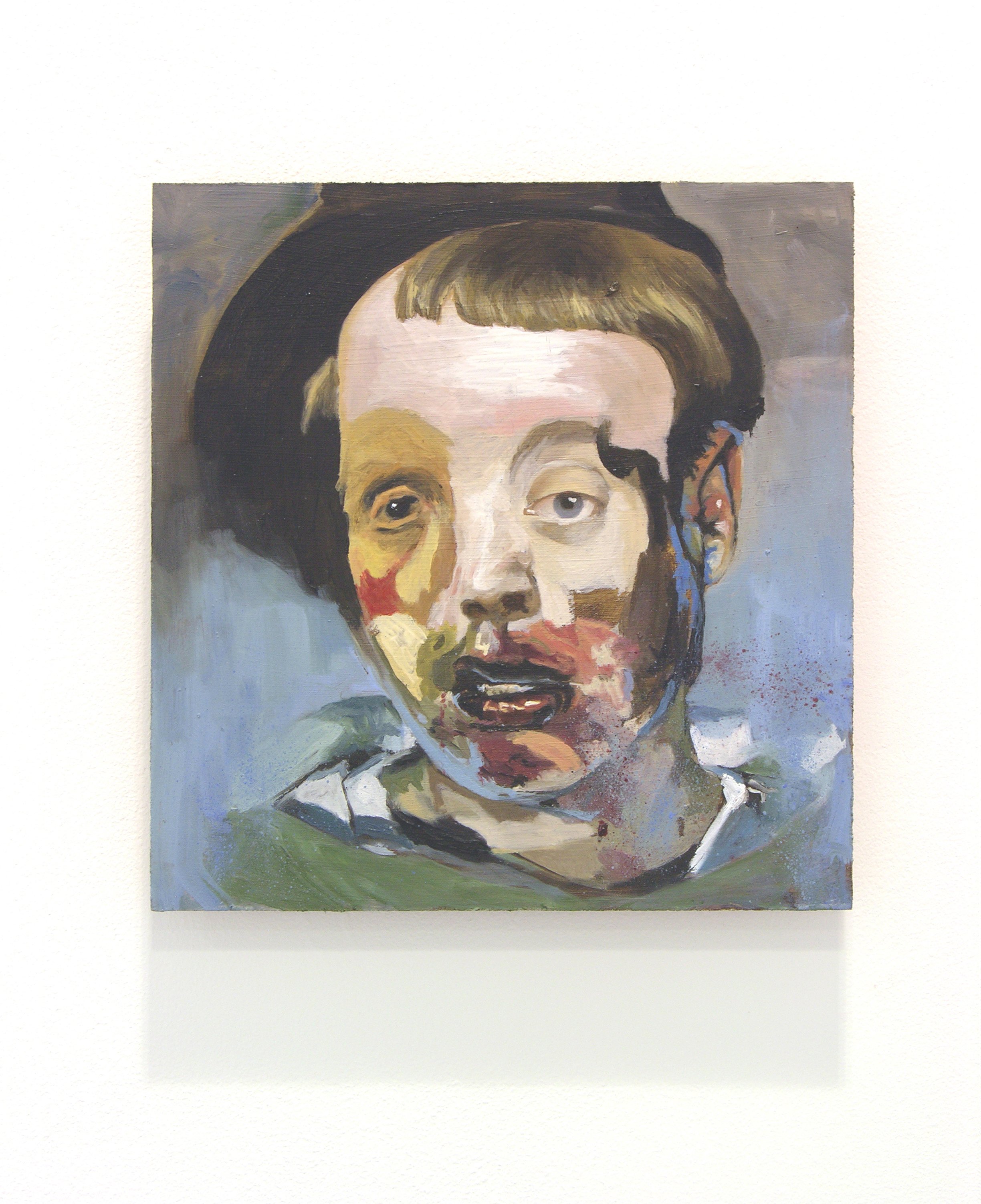

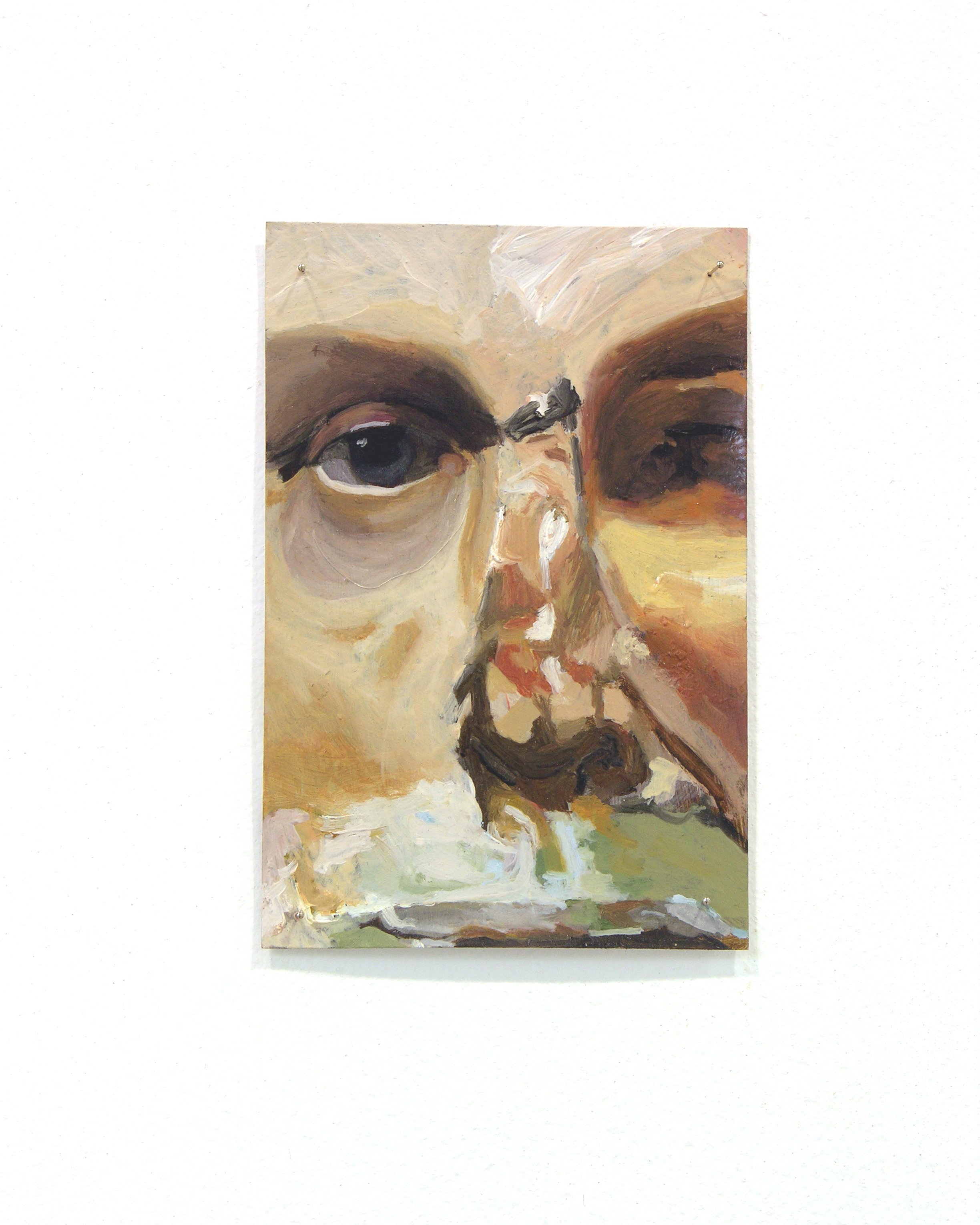

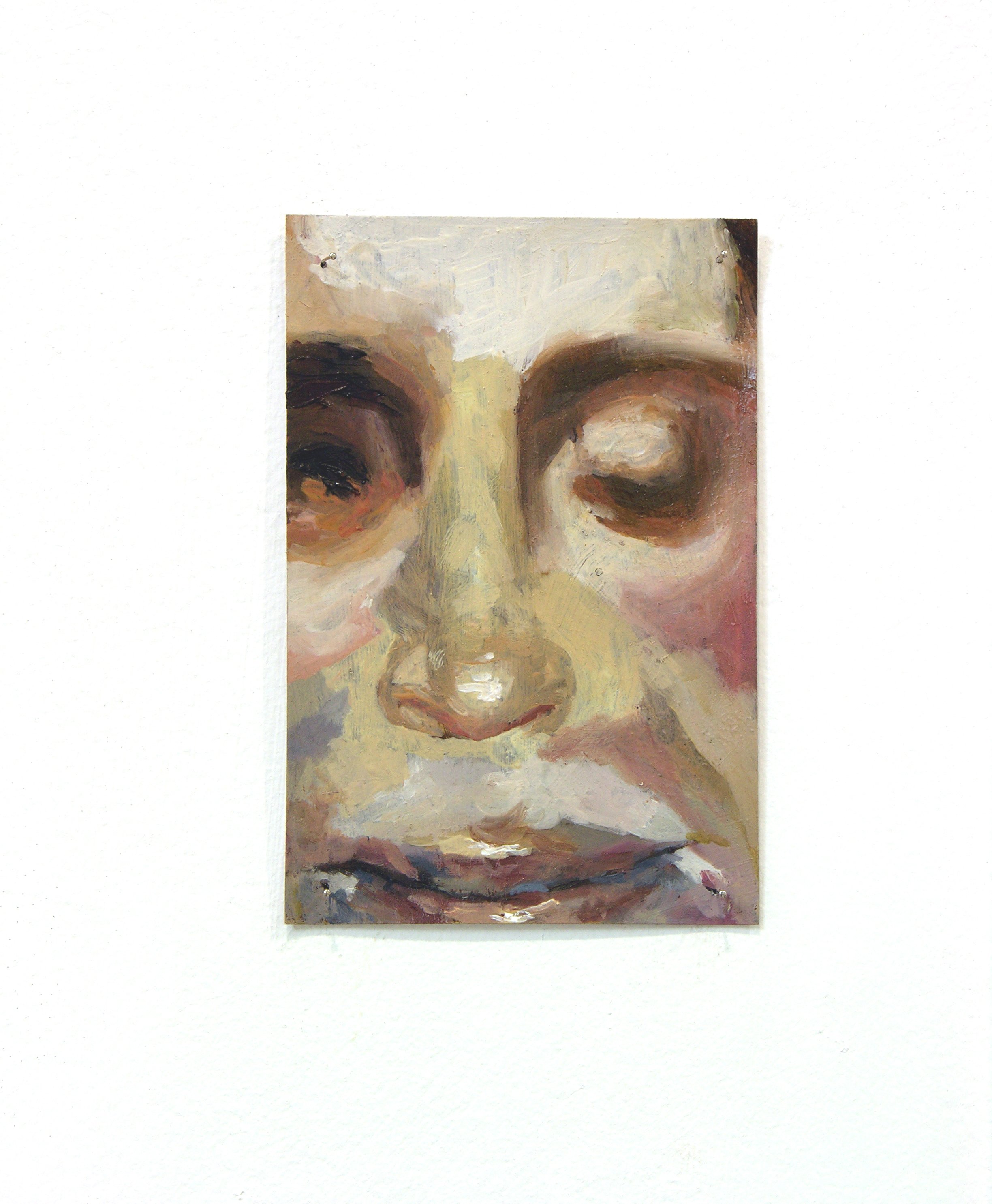

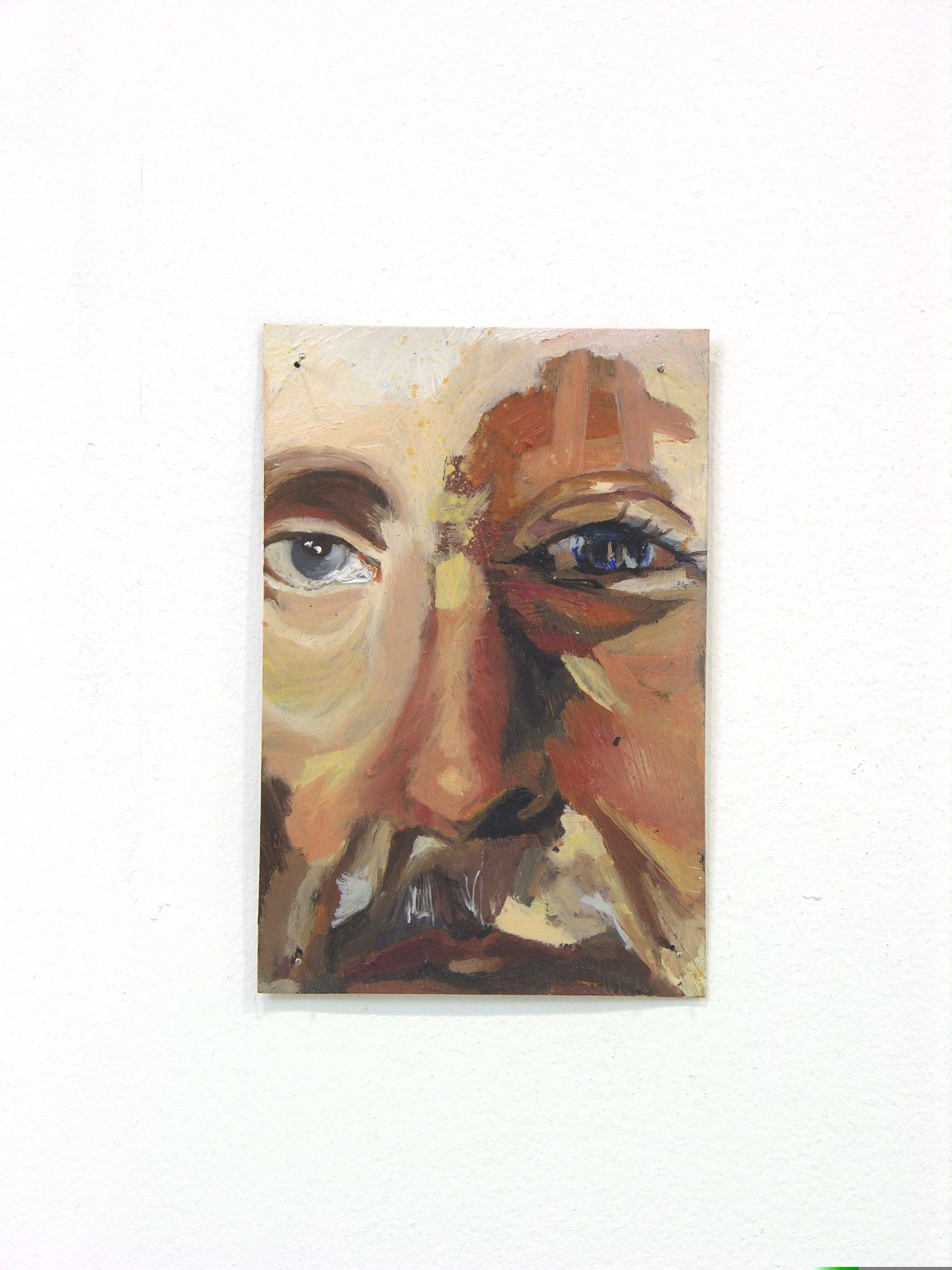

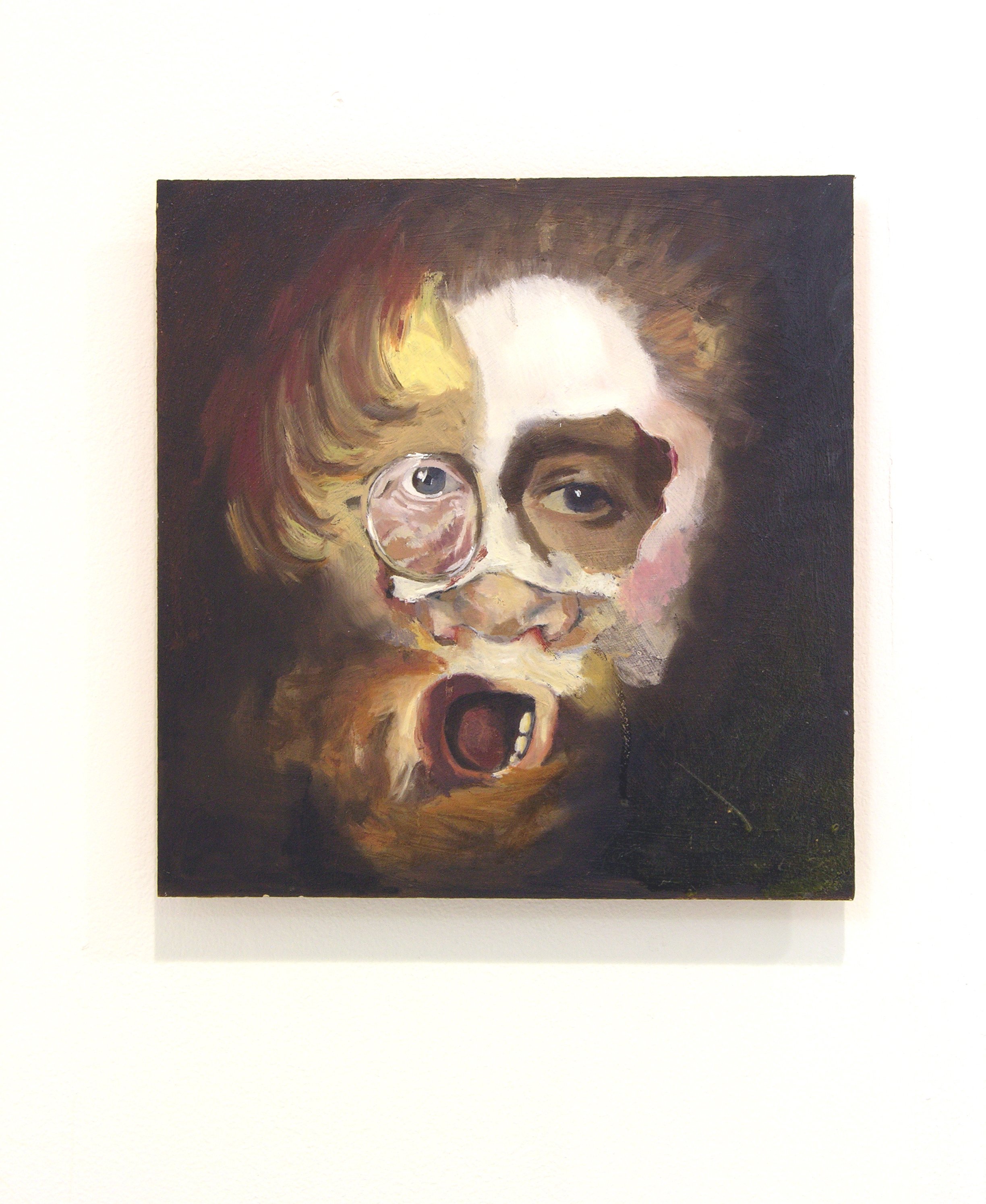

However, the painted works that accompany this text take their visual significance from a very different subject matter. The paintings depict fragments of plastic surgery patients captured by the British surgical photographer Percy Hennell (1911-1987). During the Second World War, Hennell worked alongside the plastic surgeon Harold Delf Gilles (1882-1960) to document the reconstruction process involved in this early facial surgery. These surgical operations were an attempt to re-introduce the victims of war back into civil society. Plastic surgery in this case was a means to help society deal with the disfiguring effects of war on the general population. Much like the plastic surgery operations of Gilles my painted works use the plasticity of paint to shape, shift and reconstruct new images. These images are dissections and fragments of Hennell’s documentary photographs constructed and reconstituted in oil paint. These images of fragmented bodies form newly constructed wholes that challenge society’s common acceptance of plastic surgery’s drive toward perfect beauty.

One can’t help but draw a line here between the effects of human meddling in our natural physiognomy with that of the human impact on the natural world associated with the Anthropocene. The human predilection for control over the natural brings together the colonizers of the 17th century with the normalization of plastic surgery in these glowering conceptual portraits. Small in scale the plasticity of these works augment time frames and historical precedents. The assimilation of plastic surgery with the plasticity of paint creates images of humour and pathos, by highlighting the exterior we are invited to scratch beneath the surface at the very core of the human condition.